The Dogmas of Joshua Lim

|

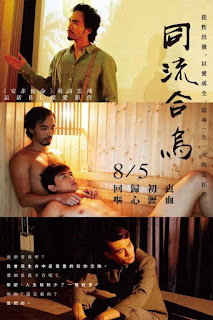

| Joshua Lim (center) - writer/director of "The Seminarian" |

Joshua Lim was born in Malaysia. The name of his company is Malacca Pictures. Malacca is a state along the western coast of Malaysia, possibly Lim's home state. He was raised in Singapore, which neighbors Malaysia, and he came to the United States in 2001. English is a dominant language in Singapore, so settling here probably wasn't so bad for him, although his Malaysian accent was pretty strong over the phone.

He told me that he got his undergraduate degree at USC in film production. He himself went to Fuller Seminary to get his Master's. Fuller is where Lim was exposed to theology students, gay theology students, possibly going through what Ryan goes through in this movie. When asked if The Seminarian is taken from true life, Lim said that he stole from his own experiences as well as the experiences of his friends.

Talking with Lim, there were two things about The Seminarian that stood out for me. Obviously, the first is this idea of a gay theologian, which is ostensibly a contradiction in terms. A theologian is a person who studies religion. Most who object to being gay do so citing religious belief, so it's odd that a gay person would then join an organization that is obviously anti-gay.

There are a lot of gay people who are born into households where the religious belief is that homosexuality is a sin. They have no control over that. Ryan, however, is living alone. He regularly visits his mother, but he's out of her house and he has control over what school he attends. Yet, he willingly attended this seminary. It's not as horrible as one might imagine, but it is akin to him willingly walking into a lion's den. The question is why and how. Clearly, Ryan's faith is important to him, but why and how can he reconcile who he is as a gay person while in an environment that is anti-gay.

In the movie, you see Ryan fall in love with Bradley whom he meets online. Ryan is able to talk to Bradley by phone, but there is a distance between them, both physical and emotional. After some time, Ryan begins to wonder about their relationship and whether or not it's real. The relationship seems to be merely one of unrequited love where Ryan loves Bradley but Bradley doesn't love Ryan in return.

I told Lim that this idea is almost a perfect metaphor for Ryan or any religious gay person's relationship with God. Ryan has faith. He loves God, but seemingly God doesn't love him back. Just as Ryan's calls to Bradley go unanswered so do Ryan's prayers to God or so we would believe. Lim described it as "God's silent treatment of these gay Christians."

The other thing about The Seminarian that stood out for me though was the way that Lim directed it. Watching this movie, the words I used to convey how it conveys itself are calm, steady, quiet and meditative. Lim said when he screened the movie, he got mixed reactions. Some thought it was a rough cut. That's probably because the movie feels so bare bones, but it isn't spartan, at least not in its presentation. Yet, it was a bit spartan in its production.

Lim said the shoot took three-and-a-half weeks. He shot using the RED camera with a crew of about 15 people. His cinematographer and editor were friends from USC and his assistant director was a friend from Fuller. Everyone else, including most of the actors were people with whom Lim had never worked before. Actor Mark Cirillo who played Ryan was one such person.

As such, Cirillo wasn't aware of what Lim called his "dogmas." Essentially, Lim's dogmas were the rules that governed his set, while he was shooting and putting the movie together. Lim stressed that his dogmas were as strict as laws and were not to be broken. One such dogma was a ban on the cast and crew talking about the movie or the making of it. Lim said he wasn't against people socializing, but only small talk. He didn't want actors for example, asking technical questions about the RED camera. Lim said he talked to his crew and got them to understand how strict he was about these rules. Lim reinforced that if any actor broke that rule that they were to be ignored.

Lim said Cirillo in one case did break this rule and the crew were prompted to ignore him. Unknowingly or not, this made for some strange symmetry both in front of and behind the scenes of Lim's movie. Cirillo wasn't getting a response from the crew just as his character of Ryan wasn't getting a response from Bradley, at least not the response he ultimately wanted. Both Cirillo and his character were lacking in reciprocity from certain people.

But, restrictions on conversations were the minor of Lim's dogmas. He's not alone in that other film directors have acted almost God-like in their exacting of control or establishing strict rules on set. Akira Kurosawa, for example, was nicknamed "tenno," which is Japanese for "emperor." While Kurosawa could be found yelling at his actors and being tyrannical, Lim seems to be more laid back. Where Kurosawa would berate and belittle an actor in order to get him to do what he wanted, Lim would be a bit more passive aggressive. Lim told me that instead of floor marks, which most filmmakers use to let actors know where to stand, he would use art direction to force actors to go where he wanted. He would literally place furniture or other objects in certain places as to give the actor no other place to go then where he wanted.

This proved to be confusing and frustrating occasionally for the actors, but it worked. The result is a movie that is well-told and very clear from a visual and contextual standpoint. Some might call it plain or boring, but it's deliberate. Lim makes choices and his dogmas prove that. In a scene where Ryan gets a call from Bradley in his bedroom, we see a ten-minute progression that is comprised of a long one-shot that almost never cuts away from looking at Ryan. In other movies, there would have been cutaways, various angles used, and especially reaction shots from Bradley.

Yet, one of Lim's dogmas was no cutting back-and-forth in phone conversations. It might come off as lazy filmmaking. It saves the cast and crew time and saves the producer money, but that's not why Lim did it at all. He did it to further his vision. This movie is about Ryan trying to connect with someone, someone whom he can't. It's about his isolation in a sense, his lacking in reciprocity. Isolating him in a scene where we don't have cutaways or see anyone else, including Bradley fits perfectly in that theme.

The poor quality of this "film" upset me. Hitchcock did the "long one-shot" gimmick better. We have to assume that the nude scene between Ryan and Gerald, occurring with blinds open and in full view of passersby, was a dream sequence. If it was not, then this scene is not remotely believable.

ReplyDelete